Play-based learning is, essentially, to learn while at play. Although the exact definition of play continues to be an area of debate in research, including what activities can be counted as play [1], play-based learning is distinct from the broader concept of play. Learning is not necessary for an activity to be perceived as play but remains fundamental to the definition of play-based learning [2]. Within studies that have examined the benefits of play-based learning, two different types of play have been the primary focus: free play, which is directed by the children themselves, and guided play, which is play that has some level of teacher guidance or involvement.

Free play is typically described as play that is child-directed, voluntary, internally motivated, and pleasurable[3,4]. One type of free play frequently endorsed is sociodramatic play, where groups of children practice imaginative role-playing through creating and following social rules such as pretending to be different family members [5]. On the other hand, the term guided play refers to play activities with some level of adult involvement to embed or extend additional learning opportunities within the play itself [6]. A range of terminology has been used to refer to types of guided play activities (e.g., centre-based learning [7], purposefully framed play [8]); however, one distinction that can be made is who has control over the play activity: Some activities are described as teacher-directed, such as intentionally planned games [9,10], while others are described as mutually directed, where teachers get involved without taking over or transforming the activity so that both teachers and students exercise some control over the play [11,12]. One example of teacher-directed play is the modification of a children’s board game to include actions that practice numerical thinking and spatial skills [13], while one example of mutually-directed play is a teacher observing students acting out a popular movie and suggesting that the class make their own movie, which leads to creating and writing a script, researching relevant topics, and practicing different roles in a collaborative manner [14]. This distinction between free play, mutually directed play, and teacher-directed play is useful for examining the growing body of literature on different types of play-based learning.

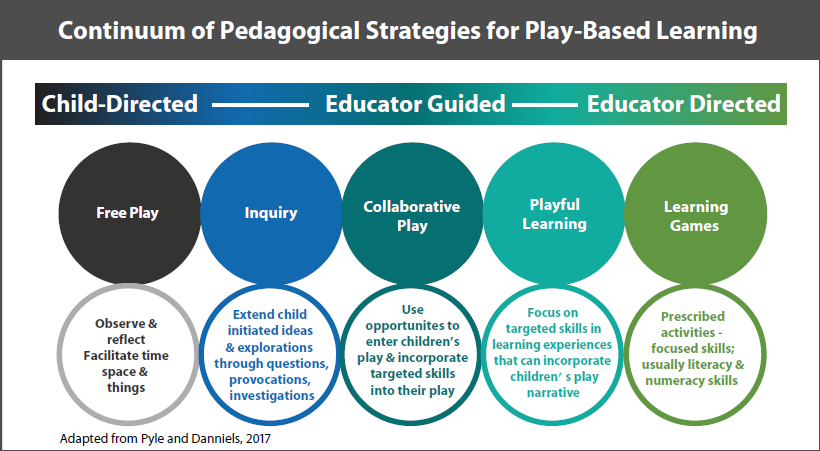

(Image source: The Play Today Handbook, see suggested books below)

(Image source: The Play Today Handbook, see suggested books below)

Play-based learning can be described along a continuum from free play, to inquiry, collaborative play, playful learning and learning games. The continuum of play-based learning incorporates the types of play alongside strategies to maximise learning opportunities.

Play that is directed by children allows them to take the lead and to engage and collaborate with each other. They take the lead and engage with the world around them. Play that is extended by conversations and educator resources can extend children’s learning. Play directed by educators with a focus on “just-in-time” instruction give children the cultural tools they need to deepen and widen their play and learning. Children and educators become a community of learners.

The continuum of play-based learning is an alternative to simply alternating direct academic instruction with free-play periods. Instead, educators can intentionally design play-based learning experiences from across the continuum with varying degrees of child direction and educator guidance. The type of program and who the children and educators are will influence how the continuum is used.

(Image source: online)

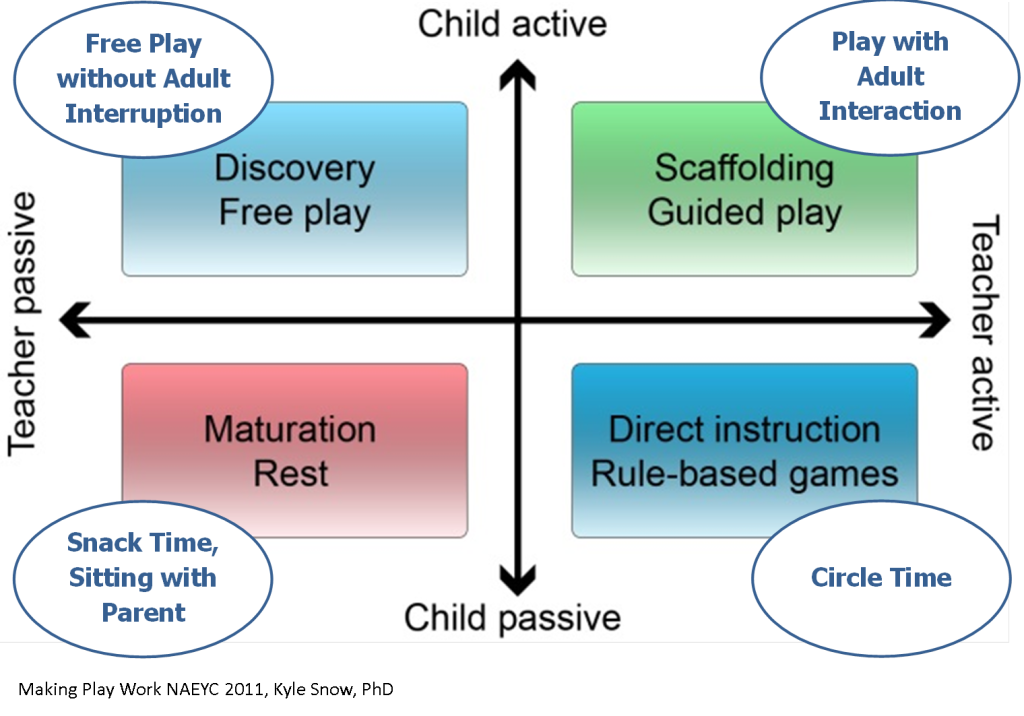

In this diagram by Kyle Snow, he divides four types of learning up by whether the teacher and child are active or passive. Whatever classes or daycare your child attends, it’s worth thinking about whether there are opportunities for all four types of learning.

Play is Essential for Learning – research review

Examinations of play-based learning in early education tend to be approached from two differing viewpoints: one focused on the benefits of play for developmental learning [15] and one focused on the benefits of play for academic learning [16]. Developmental learning includes areas such as social-emotional skills, general cognitive development, and self-regulation abilities. Articles focused on the developmental benefits of play-based learning have frequently endorsed the important role of child-directed free play in the classroom. These researchers have highlighted concerns regarding decreases in free play time due to an increased focus on meeting academic benchmarks through teacher-directed instruction [17]. For example, it has been proposed that children construct knowledge about the world and practice problem-solving skills during times of child-led exploration at different play centers [18].

Some studies have found that students engage in more effective problem-solving behaviours in child-directed play conditions than in more formal, teacher-directed settings [19,20]. Child-directed play with peers has been highlighted as an important endeavour for children to develop social and emotional competencies, such as leading and following rules, resolving conflicts, and supporting the emotional well-being of others [15]. Providing children with opportunities to negotiate and follow rules during play has also been connected to the development of self-regulation skills [21]. Many developmental learning benefits have been linked to child-directed free play contexts where educators take on an indirect or passive role, such as one who observes or prepares the environment to encourage free play [22]. Alternatively, research focused on play and academic learning has examined how play-based activities impact student learning in academic subject areas such as literacy and mathematics. These researchers tend to promote the use of mutually directed and teacher-directed play activities to support academic learning, where educators take an active role in the play such as leading pre-designed games, collaborating with students, and intervening in child-led play to incorporate learning targets [9,23,24]. Proponents of play-based learning for academic growth have argued that play-based strategies can be used to teach prescribed academic goals in an engaging and developmentally appropriate manner [24,25]. From this perspective, free play alone is often considered to be insufficient to promote academic learning, and so active teacher involvement in play is critical [9].

Recent research has supported this type of play-based learning for academic development. For example, students in classrooms following a play-based EYFS maths curriculum that implemented teacher-directed games were found to outperform students in control classrooms on general assessments of mathematical skills [23]. Similarly, children following a play-based literacy curriculum centred around mutually-directed play where educators incorporated target vocabulary words into play contexts were observed to utilise these newly taught words more frequently than children taught using direct instruction[26].

Play-Based Learning at Home

Think about your family schedule for a moment. Do you have times when you’re teaching your child? Times when they are playing with you nearby, giving occasional suggestions or playing along? Times when they’re playing independently? Quiet time? A nice mix of these will help them learn and grow.

Some parents say “my child NEVER plays alone. He always wants me to play with him.” It’s wonderful when our children like us and want to spend time with us. But, it’s also good for them to learn to play on their own too. Can you choose some times each day where you say no to them and encourage them to play alone for a while. They may resist at first, but if given a moment to “get bored” and frustrated, most can find something to do.

- Suggested books+

-

“Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life,” by Peter Gray

Dr. Gray, who has been a research professor at Boston College for 30 years, discusses the critical importance of play in the lives of children and how play has been present historically in all societies. He strongly makes the case for how instrumental play is in the lives of each and every individual in order to build the skills necessary to become healthy adults. But for that to happen, we need to parent differently and allow children the freedom to choose their own path.

“Nothing we do, no amount of toys we buy or quality time or special training we give our children can compensate for the freedom we take away. The things that children learn through their own initiatives, in free play, cannot be taught in other ways.”

“Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul,” by Stuart Brown

Dr. Brown powerfully articulates the importance of and need to play throughout our entire lives, not only in our childhoods. He details some very powerful examples of adults who became depressed because their inner child had been buried under many layers of obligation and responsibility. Dr. Brown writes about the importance of—and how to reconnect with—that inner child and bring joy back into our lives!

“We are built to play and built through play. When we play, we are engaged in the purest expression of our humanity, the truest expression of our individuality. Is it any wonder that often the times we feel the most alive, those that make up our best memories, are moments of play?”

“We don’t need play all the time to be fulfilled. The truth is that in most cases, play is a catalyst. The beneficial effects of getting just a little true play can spread through our lives, actually making us more productive and happier in everything we do.”

“Most Likely To Succeed: Preparing our Kids for the Innovation Era,” by Tony Wagner and Ted Dintersmith

These two noted educational and entrepreneurial experts call for a complete transformation of our educational system that was formed a century ago primarily to produce workers effective on assembly lines. They make it clear that in today’s society where technology will replace all rote, mechanised roles, students need to be equipped with different skills and competencies to thrive and be able to provide innovative solutions to society’s difficult challenges.

“Does anyone, besides high stakes test designers, really think our kids should be spending all of their time memorizing the placement of accent marks in French vocabulary? Memorizing the definition of an isosceles triangle? Studying the definition of covalent bonds? And on and on. But when you fill up every waking hour of a teenager’s life with these drills, you don’t have time for what really counts. And you produce disengaged kids doing the most mind-numbing of tasks rather than developing the skills they’ll need to take on life’s biggest challenges.”

“How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success,” by Julie Lythcott-Haims

As dean of freshman and undergraduate advising at Stanford University, Haims saw her share of stressed-out students and parents. In her fascinating book, she discusses how overparenting and embarking on a “checklisted childhood” path robs our children of a true childhood and denies them the ability to develop the fortitude and confidence necessary to achieve fulfillment and personal success.

“Humans need some degree of weathering in order to survive the larger challenges life will throw our way. Without experiencing the rougher spots of life, our kids become exquisite, like orchids, yet are incapable, sometimes terribly incapable, of thriving in the real world on their own. Why did parenting change from preparing our kids FOR life to protecting them FROM life, which means they’re not prepared to live life on their own?”

- Play Today Handbook. Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/early-learning/teach/earlylearning/play-today-handbook.pdf

- References and bibliography+

-

- Wallerstedt C, Pramling N. Learning to play in a goal-directed practice. Early Years. 2012;32(1):5-15.

- Pyle A, Danniels E. A continuum of play-based learning: The role of the teacher in play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Education and Development. 2017;28(3):274-289.

- Ashiabi GS. Play in the preschool classroom: Its socioemotional significance and the teacher’s role in play. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2007;35(2):199-207.

- Holt NL, Lee H, Millar CA, Spence JC. ‘Eyes on where children play’: A retrospective study of active free play. Children’s Geographies. 2015;13(1):73-88.

- Elias CL, Berk LE. Self-regulation in young children: Is there a role for sociodramatic play? Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2002;17:216-238.

- Weisberg DS, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM. Guided play: Where curricular goals meet a playful pedagogy. Mind, Brain, and Education. 2013;7:104-112.

- Kotsopoulos D, Makosz S, Zambrzycha J, McCarthy K. The effects of different pedagogical approaches on the learning of length measurement in kindergarten. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2015;43:531-539.

- Cutter-Mackenzie A, Edwards S. Toward a model for early childhood environmental education: Foregrounding, developing, and connecting knowledge through play-based learning. The Journal of Environmental Education. 2013;44(3):195-213.

- Presser AL, Clements M, Ginsburg H, Ertle B. Big math for little kids: The effectiveness of a preschool and kindergarten mathematics curriculum. Early Education and Development. 2015;26:399-426.

- Wang Z, Hung LM. Kindergarten children’s number sense development through board games. The International Journal of Learning. 2010;17(8):19-31.

- Hope-Southcott L. The use of play and inquiry in a kindergarten drama centre: A teacher’s critical reflection. Canadian Children. 2013;38(1):39-46.

- McLennan DP. Classroom bird feeding. Young Children. 2012;67(5):90-93.

- Kamii C. Modifying a board game to foster kindergarteners’ logico-mathematical thinking. Young Children. 2003;58(5):20-26.

- Damian B. Rated 5 for five-year-olds. Young Children. 2005;60(2):50-53.

- Ghafouri F, Wien CA. ‘Give us a privacy’: Play and social literacy in young children. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 2005;19(4):279-291.

- Ramani GB, Eason SH. It all adds up: Learning early math through play and games. Phi Delta Kappan. 2015;96(8):27-32.

- Bowdon J. The common core’s first casualty: Playful learning. Phi Delta Kappan. 2015;96(8):33-37.

- Fredriksen BC. Providing materials and spaces for the negotiation of meaning in explorative play: Teachers’ responsibilities. Education Inquiry. 2012;3(3):335-352.

- Gmitrová V, Gmitrov J. The primacy of child-directed pretend play on cognitive competence in a mixed-age environment: Possible interpretations. Early Child Development & Care. 2004;174(3):267-279.

- McInnes K, Howard JJ, Miles GE, Crowley K. Behavioural differences exhibited by children when practicing a task under formal and playful conditions. Educational & Child Psychology. 2009;26(2):31-39.

- De La Riva S, Ryan TG. Effect of self-regulating behaviour on young children’s academic success.International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education. 2015;7(1):69-96.

- Wood LD. Holding on to play: Reflecting on experiences as a playful K-3 teacher. Young Children. 2014;69(2):48-56.

- Sharp AC, Escalante DL, Anderson GT. Literacy instruction in kindergarten: Using the power of dramatic play. California English. 2012;18(2):16-18.

- Balfanz R, Ginsburg HP, Greenes C. The ‘big math for little kids’ early childhood mathematics program.Teaching Children Mathematics. 2003;9(5):264-268.

- Sarama J, Clements DH. Mathematics in kindergarten. Young Children. 2006;61(5):38-41.

- Van Oers B, Duijkers D. Teaching in a play-based curriculum: Theory, practice and evidence of developmental education for young children. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 2013;45(4):511-534.